UNSW Gallery until 10 August

Review by Anthony Frater (Arts Wednesday)

On now at the UNSW Galleries is an exhibition that gives the viewer a unique opportunity to see some indigenous fine works of art rarely seen in such a complete and comprehensive way under the one roof, particularly in this case, works from an Indigenous community on Melville Island, one of the two Islands of the Tiwi Island group. José Da Silva, the gallery’s in-house director and senior curator, visited the community over several years, plotting and scheming in collaboration with the artists and art centre management to bring this survey exhibition to fruition.

Entitled Parlingarri Amintiya Ningani Awungarra: Old & New at Jilamara Arts, the exhibition showcases the work of many of the art centre’s current artists, there is also some new commissions in addition to what may be a first: a tribute to the late senior women of Jilamara Arts and Crafts (established in 1989, owned and governed by artists from the Milikapiti community), whose groundbreaking adaptations of jilamara elevated Tiwi art to national and international prominence. Some of these works, drawn from the community-owned Muluwurri Museum, have never been displayed outside the museum. It gives the visitor an opportunity to see how the visual language of the Tiwi Islander peoples from Melville Island evolved.

Tiwi language and culture expert Colin Heenan- Puruntatameri says, “we want people to recognise how strong our culture is. Glimpse how beautiful and complex our culture is, our families, our countries, our history, our future. We adapt, we evolve, we change, we create as we write into the future”.

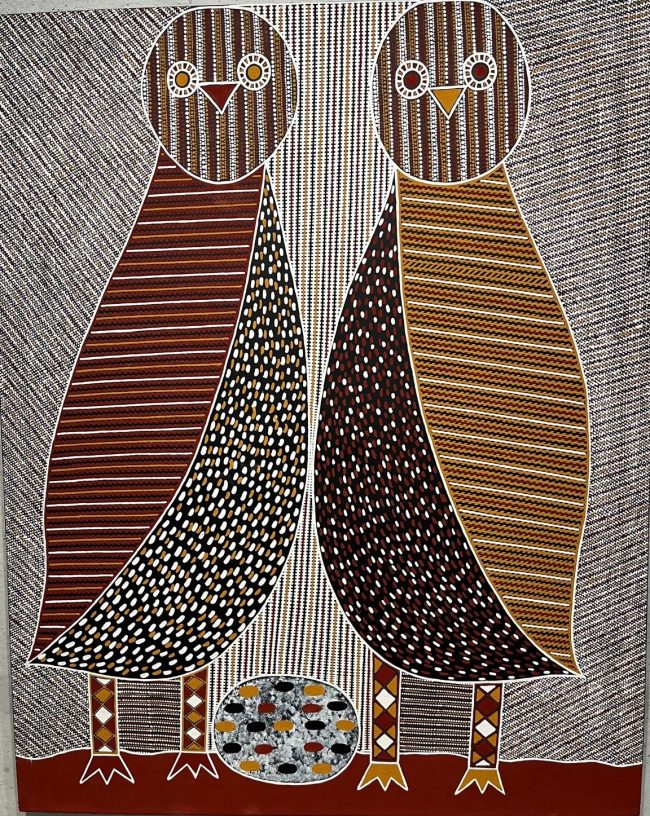

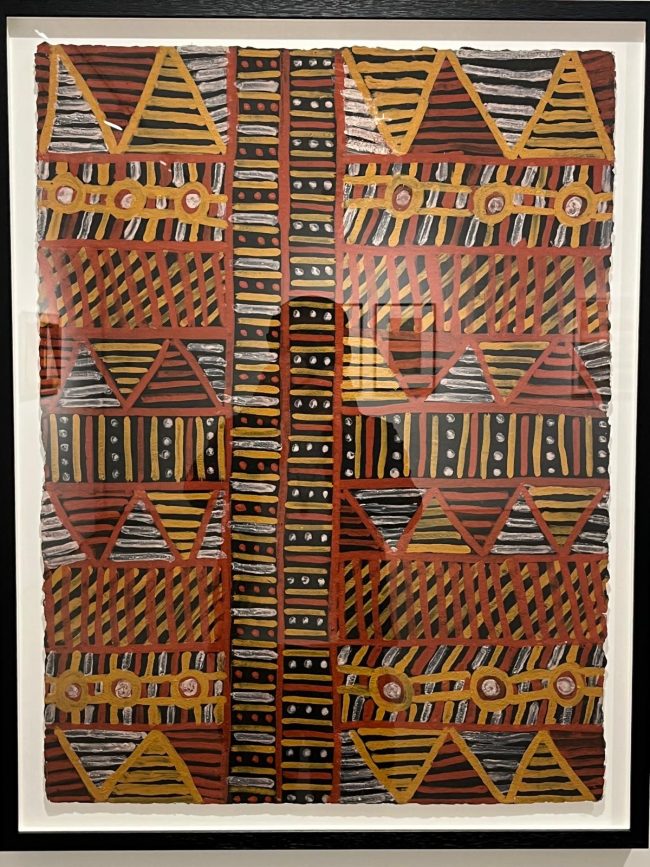

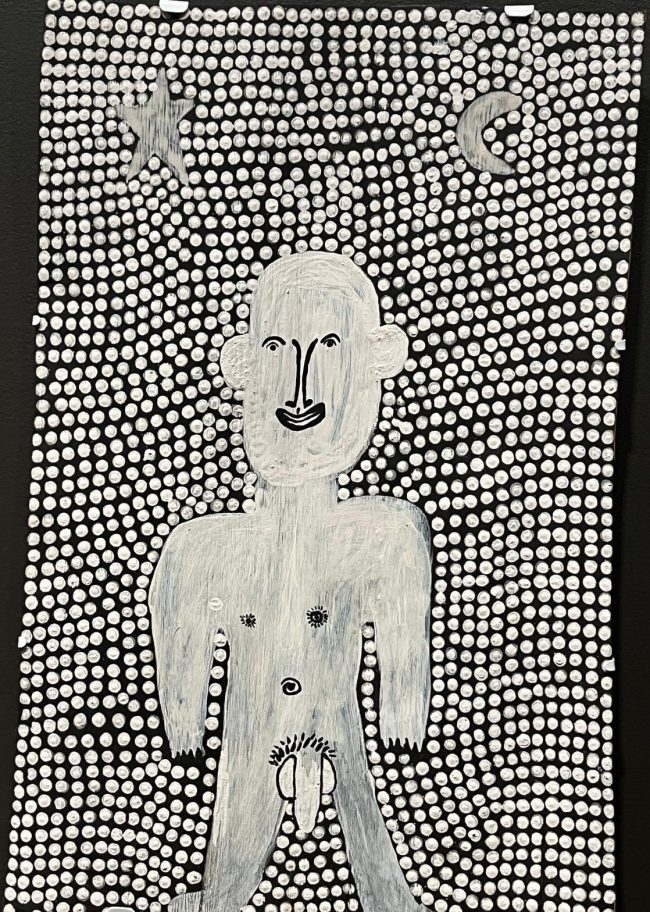

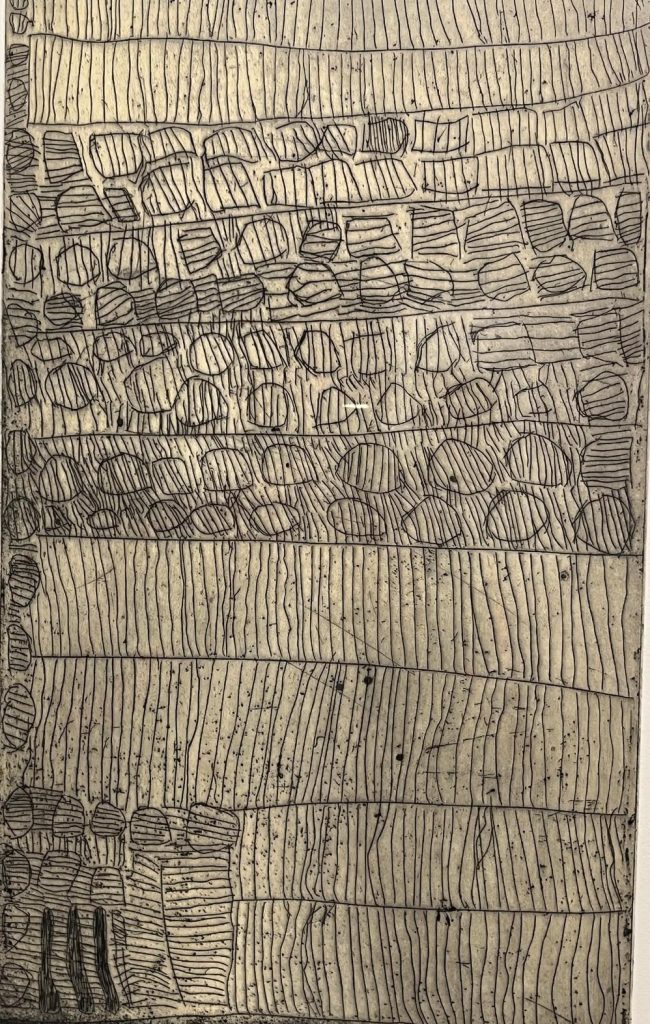

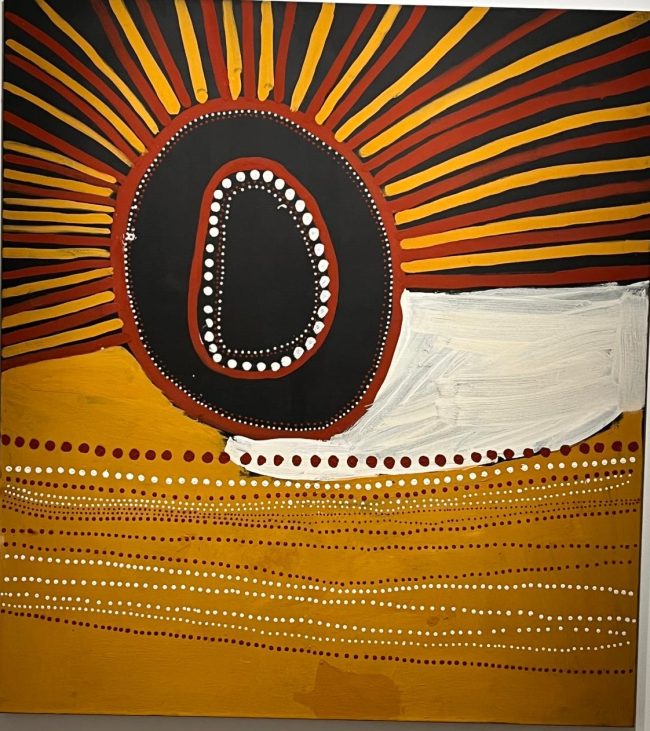

The works on display range from traditional ochre paintings on paper, canvas and stringy bark, to intricate ironwood carvings and sculptures to printmaking and video art. It’s a contemporary take on ancient ideals and ideas. Everything from clan totems and body painting designs, to creation stories all find a way from what used to be body, ground or rock wall to canvas, sculpture, print or video. Rich natural earth pigments, or ochres, are used: raw white, yellow and black; and red achieved by the Milikapiti by heating the yellow ochre to produce a rich earth red.

At this point it’s worth asking ourselves what makes Tiwi Island art unique? How do we tell the difference between indigenous art from there, and for example Arnhem Land, The Kimberley or the Central Desert. There are many similarities but generally speaking landscape/spirit of place, flora, fauna and food; the cosmos, ritual ceremonies and indigenous creation stories (the latter in the case of the Tiwi contain themes and ideas that could be straight out of a Greek myth: heavenly ascension to become forever a star, planet or moon, and winged messengers; or the Christian Bible: fratricide, adultery, original man and woman, and original sin) is all fertile ground from which to create complex and meaningful works of visual art. Each region or area is unique in terms of how subject matter is represented and what materials are used. For example works from Arnhem Land feature locally made ochre pigments on bark, Mimih Spirits, a variety of signature cross-hatching or Raak, ceremonial motifs and animal totems. The central desert artists will paint large meandering topographical works, use synthetic polymer pigments on canvas at times brightly coloured, dots representing stars, concentric circles representing place, a mirage of desert lines layered like sand dunes disappearing into the distance under an endless sky, and representations of food. In the Kimberley the enigmatic spirit man Wandjina is featured, again ochre pigments, bold representations of dramatic rock formations, and multi panelled works that contemplate the horrors of colonisation. So despite the similarities, works from different regions have unique qualities and trademarks which most often assigns them to the land on which they were made. In the case of the Tiwi, their rich opaque but shimmering ochre pigments on stringy bark board, the telltale markings created by the use of the Tiwi painting comb, or, kayimwagakimi, ironwood carvings or sculptures, and ancestral totems (birds such as the owl) that guide them – omens to take note of.

The exhibitions first room features the sun, moon and stars, they can be seen before entering, the viewer is immediately struck from afar by the rich earthy ochres and upon entering it’s like we’ve left the world behind and entered a space where ancient meets new, where what was before is no more – it’s just about here and now. It’s an aesthetic handed down, albeit evolved, through the generations over thousands and thousands of years. Moving through the room and onwards the exhibition builds in intensity, the viewer becomes aware of the thoughts and feelings these works evoke and ultimately, what we might learn.

So from the obvious physical presence of the artworks to a deeper contemplation on things such as: the importance of indigenous art centres, inherited artistic rights, authentic works versus plagiarised copies, the motivational similarities between an ancient culture and our modern day culture, the way an early science plays out based around the waxing and waning of nature and being in tune with the sounds, the feel, and changes of the earth – these practicalities, these tangibles are stacked up against a more intangible philosophy inherent to all things metaphysical: just because you can’t see it doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist; and finally but by no means least, the vast infinite cosmos.

What is it the artists, the curator and significant others want us to think about when we see these works? At this point it’s worth a brief exploration of each of the above observations.

Firstly, Art Centres play a vital role in indigenous communities all over the country in terms of them almost being collection and archival centres on the one hand in everything from history and heritage, law, legacy and culture to an outward looking institution via its chief mission in the promotion of culture via the distribution and sale of locally made authentic fine art and crafts. Jilamara members, like at other art centres around the country, have inherent diverse artistic skills and abilities and are supported in building careers as internationally renowned artists.

Secondly no one wants to spend a lot of money on a work only to find what they’ve just bought is a worthless fake. An authentic work of indigenous art is just as easily identified by what it isn’t: painters of all kinds can be put into a studio by unscrupulous dealers and instructed to plagiarise designs and subject matter. Authentic works are imbued with sacred designs and elements that allows the artist via a long line of inheritance to paint that design or subject matter and to also reinterpret or evolve the design; its tribal law, an aesthetic passed down through the generations. A fake is simply a copy of those designs, an appropriation, but even worse the name of the artist being copied might be used – fraudulently stolen – as signatory to the work. It is a case of buyer beware, but a work authenticated as being a product of a legitimate indigenous art centre will ensure authenticity and value – provenance is essential.

Science too plays a role: being aware enough and in tune with nature to recognise environmental changes that signify the coming of certain naturally occurring events – scientific because these are learnt observable facts, evidence based facts that lead time and time again to the same outcome. These events might result or dictate where you live, where you need to move to, what you will eat and drink, it’s all about how it affects your activities of daily living and understanding pertinent facts that are essential to survival and adaption. If we look hard enough this is all in the works we see in this exhibition: images that represent meditations upon physical presence, place, culture and country.

The natural and super natural worlds also influence Australian Indigenous art, just like it influences much of human endeavour. Metaphysics is a branch of philosophy that explores fundamental questions about the universe, knowledge and being. Reality and existence often focusses on concepts beyond the realm of physical observation; it’s about adapting in order to understand the underlying principals and structures of not just here but the universe and to find a place within it, indigenous peoples who have prevailed or simply survived over so many thousands of years were not able to do it without being willing or cognisant of these essential core mysteries and understandings.

These somewhat romanic ideas inform indigenous art practice, specifically here the artists of the Tiwi Islands – ideas borne out of thousands of years of meditation upon the soul of their natural environment, their complex social systems and beliefs; back then scant shelter but enough, living rough under the stars, sun and moon, fire at dusk, fire at sunrise, a cosmos out there but here under an infinite great big earthly sky, dreaming dreaming dreaming of now, then, the future and another time.

Finally, the exhibition ties tradition and contemporary practice together – each piece a trace of cultural lineage, Indigenous law and identity. They act as cultural continuity that embody ecological wisdom and spirit passed down through generations. This truly is a rare opportunity and the exhibition is on now.

UNSW Galleries

on Bidjigal & Gadigal Country

Cnr Oxford Street & Greens Road Paddington NSW 2021

24 May – 10 August 2025

Free entry

Wednesday – Friday (10am – 5pm) Saturday – Sunday (12pm – 5pm) (Closed on public holiday

Listen to a conversation with two of the artists, Patrick Freddy Puruntatamer and Arthurina Moreen below:

Share "Review: Parlingarri Amintiya Ningani Awungarra: Old & New at Jilamara Arts"

Copy